4. Proofs with structure, II

In the course of Chapter 2, we studied the logical symbols \(\lor\), \(\land\) and \(\exists\), which allow complicated mathematical statements to be built up from simpler ones. For each such symbol, we learned its “grammar”: the rule for using it when it appears in a hypothesis and the rule for using it when it appears in the goal. This grammar is called natural deduction.

This chapter finishes the work started in Chapter 2. We learn the grammar of the remaining logical symbols: \(\forall\), \(\to\), and \(\lnot\). We also learn the grammar of two other logical symbols, \(\leftrightarrow\) and \(\exists!\), which are less fundamental because they can be defined in terms of the other ones.

4.1. “For all” and implication

4.1.1. Example

Problem

Let \(a\) be a real number and suppose that for all real numbers \(x\), it is true that \(a\le x^2-2x\). Show that \(a\le -1\).

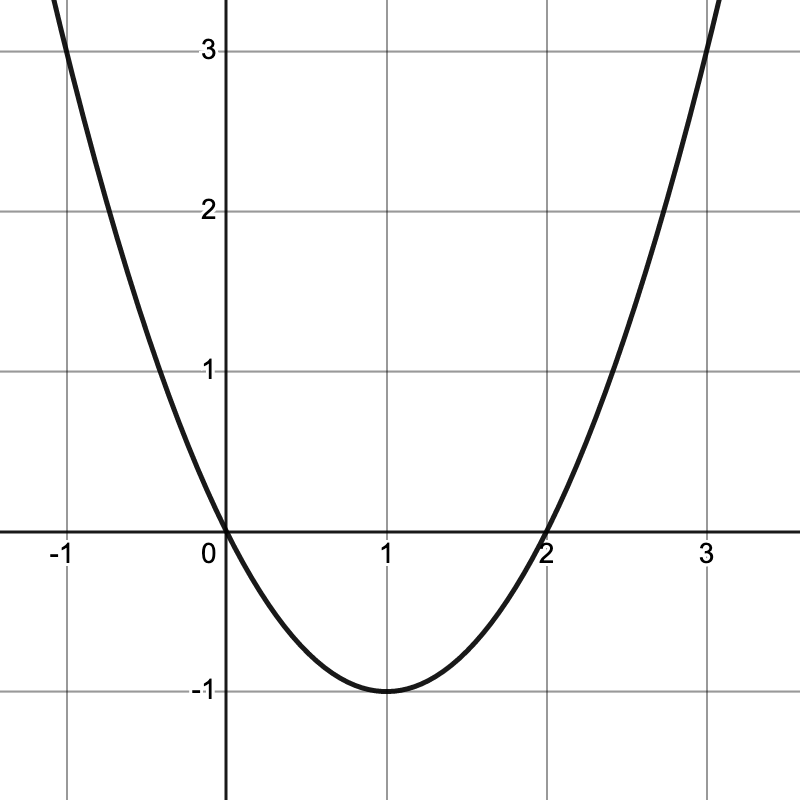

Fig. 4.1 The parabola \(y= x^2-2x\).

Specifying that a formula or predicate is meant to be true for all values of a variable \(x\),

like we did with \(a\le x^2-2x\) in the above problem, is called universally quantifying over

the variable \(x\). It is expressed symbolically as ∀.

To use a hypothesis with a universal quantifier, you may want to “specialize” its use to one particular variable. For example, in the solution below, we use the special case of the hypothesis in which \(x\) is set to 1.

Solution

In Lean, perform this specialization using the apply tactic.

example {a : ℝ} (h : ∀ x, a ≤ x ^ 2 - 2 * x) : a ≤ -1 :=

calc

a ≤ 1 ^ 2 - 2 * 1 := by apply h

_ = -1 := by numbers

4.1.2. Example

Problem

Let \(n\) be a natural number which is a factor of every natural number \(m\). Show that \(n=1\).

Solution

Since \(n\) is a factor of every natural number, it is a factor of \(1\). Also notice that \(1\) is positive. So we can invoke the size bounds on factors discussed in Example 3.2.7 and Example 3.2.8: \(n\le 1\) and \(1 \le n\). Therefore \(n=1\).

For the Lean proof, we recall that the bound from Example 3.2.7 is in Lean as

Nat.le_of_dvd, and the bound from Example 3.2.8 is in Lean as

Nat.pos_of_dvd_of_pos.

example {n : ℕ} (hn : ∀ m, n ∣ m) : n = 1 := by

have h1 : n ∣ 1 := by apply hn

have h2 : 0 < 1 := by numbers

apply le_antisymm

· apply Nat.le_of_dvd h2 h1

· apply Nat.pos_of_dvd_of_pos h1 h2

4.1.3. Example

Problem

Let \(a\) and \(b\) be real numbers and suppose that every real number \(x\) is either at least \(a\) or at most \(b\). Show that \(a \le b\).

Solution

Consider the real number \(\frac {a+b}{2}\). It is either at least \(a\) or at most \(b\).

Case 1: \(\frac {a+b}{2} \geq a\). Then

Case 2: \(\frac {a+b}{2} \leq b\). Then

example {a b : ℝ} (h : ∀ x, x ≥ a ∨ x ≤ b) : a ≤ b := by

sorry

4.1.4. Example

Problem

Let \(a\) be real number whose square is at most 2, and which is greater than or equal to any real number whose square is at most 2. 1 Let \(b\) be another real number with the same two properties. Prove that \(a=b\).

Consider the hypothesis in this problem that

\(a\) is greater than or equal to any real number whose square is at most 2.

Implicitly, there is a universal quantification (“any real number”), and also an implication, so a more pedantic version of this hypothesis would be

for all real numbers \(y\), if \(y^2\le 2\) then \(y\le a\).

We can specialize such a hypothesis to any particular choice of \(y\) for which the antecedent \(y^2\le 2\) is true.

Solution

Since \(a^2\le 2\), and \(b\) is greater than or equal to any real number whose square is at most 2, \(a \le b\).

Since \(b^2\le 2\), and \(a\) is greater than or equal to any real number whose square is at most 2, \(b \le a\).

Therefore \(a=b\).

In Lean, an implication is expressed using the symbol →. The tactic apply works for

hypotheses featuring implications. In the proof below, the goal state before apply hb2 is

a b: ℝ

ha1 : a ^ 2 ≤ 2

hb1 : b ^ 2 ≤ 2

ha2 : ∀ (y : ℝ), y ^ 2 ≤ 2 → y ≤ a

hb2 : ∀ (y : ℝ), y ^ 2 ≤ 2 → y ≤ b

⊢ a ≤ b

and the goal state after it is

a b : ℝ

ha1 : a ^ 2 ≤ 2

hb1 : b ^ 2 ≤ 2

ha2 : ∀ (y : ℝ), y ^ 2 ≤ 2 → y ≤ a

hb2 : ∀ (y : ℝ), y ^ 2 ≤ 2 → y ≤ b

⊢ a ^ 2 ≤ 2

The hypothesis ∀ (y : ℝ), y ^ 2 ≤ 2 → y ≤ b has been applied to the goal a ≤ b, leaving

the hopefully-easier goal a ^ 2 ≤ 2: proving the antecedent of the implication.

Fill in the second part of the proof.

example {a b : ℝ} (ha1 : a ^ 2 ≤ 2) (hb1 : b ^ 2 ≤ 2) (ha2 : ∀ y, y ^ 2 ≤ 2 → y ≤ a)

(hb2 : ∀ y, y ^ 2 ≤ 2 → y ≤ b) :

a = b := by

apply le_antisymm

· apply hb2

apply ha1

· sorry

4.1.5. Example

Problem

Show that there exists a real number \(b\) such that for every real number \(x\), it is true that \(b \le x^2-2x\).

Notice that in this problem a universally quantified statement appears in the goal: “for every real number \(x\), ….”

Solution

We show that -1 has this property. Indeed, let \(x\) be a real number; then

We solve the problem by formally introducing a particular, arbitrary real number \(x\) (“let

\(x\) be a real number”) and proving the desired statement for that \(x\). In Lean this

argument is performed by the tactic intro. Before the use of this tactic, the goal state is

⊢ ∀ (x : ℝ), -1 ≤ x ^ 2 - 2 * x

After the use of this tactic, the goal state is

x : ℝ

⊢ -1 ≤ x ^ 2 - 2 * x

example : ∃ b : ℝ, ∀ x : ℝ, b ≤ x ^ 2 - 2 * x := by

use -1

intro x

calc

-1 ≤ -1 + (x - 1) ^ 2 := by extra

_ = x ^ 2 - 2 * x := by ring

4.1.6. Example

Problem

Show that there exists a real number \(c\) such that for all real numbers \(x\) and \(y\), if \(x^2+y^2\le 4\), then \(x+y\geq c\).

Here the goal contains universal quantification over \(x\) and \(y\), as well as an implication: “if \(x^2+y^2\le 4\), then ….” In solving the problem, we formally introduce the variables \(x\) and \(y\) and also the hypothesis \(x^2+y^2\le 4\) which they are assumed to satisfy:

Solution

We show that -3 has this property. Indeed, let \(x\) and \(y\) be real numbers and suppose that \(x^2+y^2\le 4\). Then

So \(x + y \geq -3\) (and also \(x + y \leq 3\)).

In Lean, the introduction of both the variables \(x\) and \(y\) and the hypothesis

\(x^2+y^2\le 4\) is done using the intro tactic. To deduce from

\((x + y) ^ 2 \le 3 ^ 2\) that \(-3 ≤ x + y\) and \(x + y ≤ 3\), you will need to use

the lemma

lemma abs_le_of_sq_le_sq' (h : x ^ 2 ≤ y ^ 2) (hy : 0 ≤ y) : -y ≤ x ∧ x ≤ y :=

which we previously saw in Example 2.4.2.

example : ∃ c : ℝ, ∀ x y, x ^ 2 + y ^ 2 ≤ 4 → x + y ≥ c := by

sorry

4.1.7. Example

Definition

A property is true for all sufficiently large integers \(n\), if there exists an integer \(N\), such that that property is true for all integers \(n\geq N\).

Likewise for rational numbers, real numbers, ….

Problem

Show that for all sufficiently large integers \(n\), it is true that \(n ^ 3 ≥ 4n ^ 2 + 7\).

In the solution that follows, “For all \(n\geq 5\)” is a shorter way of expressing, “Let \(n\) be an integer and suppose that \(n\geq 5\)”.

Solution

For all \(n\geq 5\),

I have provided the notation forall_sufficiently_large to express this and similar problems in

Lean.

example : forall_sufficiently_large n : ℤ, n ^ 3 ≥ 4 * n ^ 2 + 7 := by

dsimp

use 5

intro n hn

calc

n ^ 3 = n * n ^ 2 := by ring

_ ≥ 5 * n ^ 2 := by rel [hn]

_ = 4 * n ^ 2 + n ^ 2 := by ring

_ ≥ 4 * n ^ 2 + 5 ^ 2 := by rel [hn]

_ = 4 * n ^ 2 + 7 + 18 := by ring

_ ≥ 4 * n ^ 2 + 7 := by extra

4.1.8. Example

Definition

A natural number \(p\) is prime, if it is at least \(2\), and the only factors of \(p\) are \(1\) and \(p\).

def Prime (p : ℕ) : Prop :=

2 ≤ p ∧ ∀ m : ℕ, m ∣ p → m = 1 ∨ m = p

Problem

Show that 2 is prime.

Solution

Clearly \(2 \le 2\). Let \(m\) be a factor of \(2\). Since \(2\) is positive, by the size bounds on factors discussed in Example 3.2.7 and Example 3.2.8, we have that \(m \le 2\) and \(1 \le m\). The only natural numbers \(m\) satisfying \(m \le 2\) and \(1 \le m\) are \(1\) and \(2\), so as required \(m=1\) or \(m=2\).

One new technique used in this solution is to observe from numeric bounds on a natural number (like

\(m \le 2\) and \(1 \le m\) here) that there are finitely many possibilities (here,

\(m=1\) or \(m=2\).) In Lean, we use the tactic interval_cases for this kind of

argument. It also works for integers, but it doesn’t work for rational numbers or real numbers –

why?

example : Prime 2 := by

constructor

· numbers -- show `2 ≤ 2`

intro m hmp

have hp : 0 < 2 := by numbers

have hmp_le : m ≤ 2 := Nat.le_of_dvd hp hmp

have h1m : 1 ≤ m := Nat.pos_of_dvd_of_pos hmp hp

interval_cases m

· left

numbers -- show `1 = 1`

· right

numbers -- show `2 = 2`

This lemma is available for future use in Lean under the name prime_two.

4.1.9. Example

You might be wondering how to prove that a natural number \(p\) is not prime. The idea is to show that it can be expressed as a nontrivial product.

Problem

Show that 6 is not prime.

Solution

\(6=2\cdot 3\), so \(2 \mid 6\). But \(2 \ne 1\) and \(2 \ne 6\).

We will prove this test carefully in Example 4.5.7. For now, feel free to

use it. In Lean the lemma name is not_prime.

example : ¬ Prime 6 := by

apply not_prime 2 3

· numbers -- show `2 ≠ 1`

· numbers -- show `2 ≠ 6`

· numbers -- show `6 = 2 * 3`

4.1.10. Exercises

Let \(a\) be a rational number and suppose that for all rational numbers \(b\), \(a\ge -3+4b-b^2\). Show that \(a\ge 1\).

example {a : ℚ} (h : ∀ b : ℚ, a ≥ -3 + 4 * b - b ^ 2) : a ≥ 1 := sorry

Let \(n\) be an integer and suppose that every integer \(m\) between 1 and 5 is a factor of \(n\). Show that 15 is a factor of \(n\). (You may need to review Section 3.5.)

example {n : ℤ} (hn : ∀ m, 1 ≤ m → m ≤ 5 → m ∣ n) : 15 ∣ n := by sorry

Show that there exists a natural number \(n\) such that every natural number \(m\) is at least \(n\).

example : ∃ n : ℕ, ∀ m : ℕ, n ≤ m := by sorry

Show that there exists a real number \(a\), such that for all real numbers \(b\), there exists a real number \(c\), such that \(a + b < c\).

example : ∃ a : ℝ, ∀ b : ℝ, ∃ c : ℝ, a + b < c := by sorry

Show that for all sufficiently large real numbers \(x\), \(x ^ 3 + 3 x ≥ 7 x ^ 2 + 12\).

example : forall_sufficiently_large x : ℝ, x ^ 3 + 3 * x ≥ 7 * x ^ 2 + 12 := by sorry

Show that 45 is not prime.

You may use the Lean lemma

not_prime, as in Example 4.1.9.example : ¬(Prime 45) := by sorry

Footnotes

- 1

That is, \(a\) is maximal in the set of real numbers whose square is at most 2.

4.2. “If and only if”

4.2.1. Example

Problem

Let \(a\) be a rational number. Show that \(3a+1\le 7\) if and only if \(a\le 2\).

The phrase “if and only if” means exactly what it sounds like. In this problem we have to show (1) if \(3a+1\le 7\) then \(a\le 2\) and (2) if \(a\le 2\) then \(3a+1\le 7\).

Solution

First, suppose that \(3a+1\le 7\). Then

Conversely, suppose that \(a\le 2\). Then

In handwritten work, it is quite common to annotate the two directions with the symbols \(\Rightarrow\) and \(\Leftarrow\) respectively:

Solution

\(\Rightarrow\) Suppose that \(3a+1\le 7\). Then …

\(\Leftarrow\) Suppose that \(a\le 2\). Then …

This is recommended for homework, tests, writing on the blackboard, etc. In more formal writing (such as this book) we omit such symbols and instead use words like “First” and “Conversely” to signal the different parts of the proof.

In Lean, an “if and only if” is stated with the bi-implication symbol ↔. Since, under the hood,

an “if and only if” is an “and” statement, we use the same tactic as for “and” goals:

constructor.

example {a : ℚ} : 3 * a + 1 ≤ 7 ↔ a ≤ 2 := by

constructor

· intro h

calc a = ((3 * a + 1) - 1) / 3 := by ring

_ ≤ (7 - 1) / 3 := by rel [h]

_ = 2 := by numbers

· intro h

calc 3 * a + 1 ≤ 3 * 2 + 1 := by rel [h]

_ = 7 := by numbers

4.2.2. Example

Let’s modify Example 3.5.1 to be an if-and-only-if problem. Now there are two things to prove, one of which we did before.

Problem

Let \(n\) be an integer. Show that \(5n\) is a multiple of \(8\) if and only if \(n\) is.

Solution

Suppose that \(8\mid 5n\). Then there exists an integer \(a\) such that \(5n=8a\). So

so \(8\mid n\).

Conversely, suppose that \(8\mid n\). Then there exists an integer \(a\) such that \(n=8a\). So

so \(8\mid 5n\).

example {n : ℤ} : 8 ∣ 5 * n ↔ 8 ∣ n := by

constructor

· intro hn

obtain ⟨a, ha⟩ := hn

use -3 * a + 2 * n

calc

n = -3 * (5 * n) + 16 * n := by ring

_ = -3 * (8 * a) + 16 * n := by rw [ha]

_ = 8 * (-3 * a + 2 * n) := by ring

· intro hn

obtain ⟨a, ha⟩ := hn

use 5 * a

calc 5 * n = 5 * (8 * a) := by rw [ha]

_ = 8 * (5 * a) := by ring

4.2.3. Example

Problem

Show that an integer \(n\) is odd, if and only if it is congruent to 1 modulo 2.

Solution

First, suppose that \(n\) is odd. Then there exists an integer \(k\) such that \(n=2k+1\). Therefore \(n-1=2k\), so \(n-1\) is divisible by 2, so \(n\equiv 1\mod 2\).

Conversely, suppose that \(n\equiv 1\mod 2\). Then \(2\mid n -1\), so there exists an integer \(k\) such \(n-1=2k\). Thus \(n=2k+1\) and so \(n\) is odd.

We name this example Int.odd_iff_modEq for future use.

theorem odd_iff_modEq (n : ℤ) : Odd n ↔ n ≡ 1 [ZMOD 2] := by

constructor

· intro h

obtain ⟨k, hk⟩ := h

dsimp [Int.ModEq]

dsimp [(· ∣ ·)]

use k

addarith [hk]

· sorry

4.2.4. Example

Now do the same to characterise evenness.

Problem

Show that an integer \(n\) is even, if and only if it is congruent to 0 modulo 2.

theorem even_iff_modEq (n : ℤ) : Even n ↔ n ≡ 0 [ZMOD 2] := by

constructor

· intro h

obtain ⟨k, hk⟩ := h

dsimp [Int.ModEq]

dsimp [(· ∣ ·)]

use k

addarith [hk]

· sorry

4.2.5. Example

The high school concept of “solving” equations represents an “if and only if” problem: to solve an equation, you state a list of numbers and prove that they satisfy the equation and no other numbers do.

Problem

Let \(x\) be a real number. Show that \(x ^ 2 + x - 6 = 0\), if and only if \(x = -3\) or \(x = 2\).

Solution

First, suppose that \(x ^ 2 + x - 6 = 0\). Then

so either \(x+3=0\) or \(x-2=0\). If the former, \(x=-3\); if the latter, \(x=2\).

Conversely, if \(x=-3\) then

and if \(x=2\) then

example {x : ℝ} : x ^ 2 + x - 6 = 0 ↔ x = -3 ∨ x = 2 := by

sorry

4.2.6. Example

Problem

Let \(a\) be an integer. Show that \(a^2-5a+5 \le -1\), if and only if \(a\) is 2 or 3.

Solution

First, suppose that \(a^2-5a+5 \le -1\). Then

so \(-1\le 2a-5\le 1\). Therefore \(2 \cdot 2 \le 2a\), so \(2 \le a\), and similarly \(2a ≤ 2 \cdot 3\), so \(a \le 3\). Since \(2\le a\le 3\), \(a\) is 2 or 3.

Conversely, if \(a=2\) then

and if \(a=3\) then

example {a : ℤ} : a ^ 2 - 5 * a + 5 ≤ -1 ↔ a = 2 ∨ a = 3 := by

sorry

4.2.7. Example

Some library lemmas have the form of an “if and only if”. This is convenient because they take the place of two ordinary lemmas, one for each direction.

Problem

Let \(n\) be an integer and suppose \(n ^ 2 - 10 n + 24 = 0\). Show that \(n\) is even.

Solution

We have

so either \(n-4=0\) or \(n-6=0\). If the former, then \(n=2\cdot 2\) so \(n\) is even; if the latter, then \(n=2\cdot 3\) so \(n\) is even.

In this problem we need to transform the fact \((n-4)(n-6)=0\) into the fact that “\(n-4=0\) or \(n-6=0\).” Previously (like in Example 2.3.4), we would have done this in Lean by inserting this fact directly into the lemma

theorem eq_zero_or_eq_zero_of_mul_eq_zero {a b : ℤ} (h : a * b = 0) : a = 0 ∨ b = 0 :=

resulting in a proof setup like this:

example {n : ℤ} (hn : n ^ 2 - 10 * n + 24 = 0) : Even n := by

have hn1 :=

calc (n - 4) * (n - 6) = n ^ 2 - 10 * n + 24 := by ring

_ = 0 := hn

have hn2 := eq_zero_or_eq_zero_of_mul_eq_zero hn1

sorry

(Exercise: finish off the proof.)

But there is also a library lemma in ↔ form, which combines eq_zero_or_eq_zero_of_mul_eq_zero

with the converse (other direction) of that statement:

theorem mul_eq_zero {a b : ℤ} : a * b = 0 ↔ a = 0 ∨ b = 0 :=

We can use an ↔ lemma in Lean with the rw tactic; it converts a hypothesis (or the goal) in

the form of the left-hand side of the ↔ to one with the form of the right-hand side.

example {n : ℤ} (hn : n ^ 2 - 10 * n + 24 = 0) : Even n := by

have hn1 :=

calc (n - 4) * (n - 6) = n ^ 2 - 10 * n + 24 := by ring

_ = 0 := hn

rw [mul_eq_zero] at hn1 -- `hn1 : n - 4 = 0 ∨ n - 6 = 0`

sorry

4.2.8. Example

Above, in Example 4.2.3, we proved that an integer is odd if and only if it

is congruent to 1 modulo 2, recording this under the name Int.odd_iff_modEq. This is now also

a convenient “if and only if” library lemma which we can use to solve problems about parity using

modulo arithmetic. As an example, let’s re-do the problem from

Example 3.1.5.

Problem

Prove that if the integers \(x\) and \(y\) are odd, then \(x+y+1\) is odd.

Solution

We will prove that if \(x\equiv 1 \mod 2\) and \(y\equiv 1 \mod 2\) then \(x+y+1\equiv 1 \mod 2\). Indeed,

example {x y : ℤ} (hx : Odd x) (hy : Odd y) : Odd (x + y + 1) := by

rw [Int.odd_iff_modEq] at *

calc x + y + 1 ≡ 1 + 1 + 1 [ZMOD 2] := by rel [hx, hy]

_ = 2 * 1 + 1 := by ring

_ ≡ 1 [ZMOD 2] := by extra

4.2.9. Example

Another way we can use the characterization of parity in terms of modular arithmetic is to prove the theorem from Example 3.1.9 whose proof we skipped.

Theorem

Every integer is either even or odd.

Proof

Let \(n\) be an integer. We do a case division according to the residue of \(n\) modulo 2.

If \(n\equiv 0\mod 2\), then \(n\) is even, and we are done.

If \(n\equiv 0\mod 2\), then \(n\) is odd, and we are done.

Write this in Lean using the lemmas Int.odd_iff_modEq and Int.even_iff_modEq from

Example 4.2.3 and Example 4.2.4, together with the

tactic mod_cases. I have written the beginning.

example (n : ℤ) : Even n ∨ Odd n := by

mod_cases hn : n % 2

· left

rw [Int.even_iff_modEq]

apply hn

· sorry

4.2.10. Exercises

Let \(x\) be a real number. Show that \(2x-1=11\) if and only if \(x=6\).

example {x : ℝ} : 2 * x - 1 = 11 ↔ x = 6 := by sorry

Let \(n\) be an integer. Show that 63 is a factor of \(n\) if and only if both 7 and 9 are.

example {n : ℤ} : 63 ∣ n ↔ 7 ∣ n ∧ 9 ∣ n := by sorry

Let \(a\) and \(n\) be integers. Show that \(a\) is a multiple of \(n\) if and only if \(a \equiv 0 \mod n\).

theorem dvd_iff_modEq {a n : ℤ} : n ∣ a ↔ a ≡ 0 [ZMOD n] := by sorry

Let \(a\) and \(b\) be integers and suppose that \(a \mid b\). Show that \(a \mid 2b^3-b^2+3b\).

Note that this appeared already as an exercise in Section 3.2. But now, using the lemma

Int.dvd_iff_modEqproved in the previous exercise, this kind of problem is much easier.example {a b : ℤ} (hab : a ∣ b) : a ∣ 2 * b ^ 3 - b ^ 2 + 3 * b := by sorry

Let \(k\) be a natural number. Show that \(k^2 \le 6\), if and only if \(k\) is 0, 1 or 2.

example {k : ℕ} : k ^ 2 ≤ 6 ↔ k = 0 ∨ k = 1 ∨ k = 2 := by sorry

4.3. “There exists a unique”

4.3.1. Example

Problem

Show that there exists a unique real number \(a\), such that \(3a+1=7\).

Solution

We will show that 2 is the unique real number with this property.

First, we show that 2 has this property. Indeed, \(3\cdot 2+1=7\).

Now, let \(y\) be a real number for which \(3y+1=7\). Then

example : ∃! a : ℝ, 3 * a + 1 = 7 := by

use 2

dsimp

constructor

· numbers

intro y hy

calc

y = (3 * y + 1 - 1) / 3 := by ring

_ = (7 - 1) / 3 := by rw [hy]

_ = 2 := by numbers

4.3.2. Example

Problem

Show that there exists a unique rational number \(x\), such that for every rational number \(a\) between 1 and 3, \((a-x)^2\le 1\).

Solution

We will show that 2 is the unique rational number with this property.

Firstly, if \(a\) is a rational number between 1 and 3, then \(-1 \le a-2 \le 1\), so by Example 2.1.7,

Now, let \(y\) be a rational number for which, for every rational number \(a\) between 1 and 3, \((a-y)^2\le 1\).

Since 1 is between 1 and 3, \((1-y)^2\le 1\), and since 3 is between 1 and 3, \((3-y)^2\le 1\).

So

Also \((y - 2) ^ 2\geq 0\), since squares are positive. Thus \((y - 2) ^ 2= 0\), so \(y - 2= 0\), and so \(y = 2\).

In Lean, the result of Example 2.1.7 is available as the lemma sq_le_sq'.

example : ∃! x : ℚ, ∀ a, a ≥ 1 → a ≤ 3 → (a - x) ^ 2 ≤ 1 := by

sorry

4.3.3. Example

Problem

Let \(x\) be a rational number, and suppose that there exists a unique rational number \(a\) such that \(a^2=x\). Show that \(x=0\).

More colloquially: the only rational number with a unique square root is 0.

Solution

We first show that \(-a=a\). Indeed,

and since \(a\) is the unique rational number such that \(a^2=x\), this means that \(-a=a\).

It follows that

So \(x=0\) also:

example {x : ℚ} (hx : ∃! a : ℚ, a ^ 2 = x) : x = 0 := by

obtain ⟨a, ha1, ha2⟩ := hx

have h1 : -a = a

· apply ha2

calc

(-a) ^ 2 = a ^ 2 := by ring

_ = x := ha1

have h2 :=

calc

a = (a - -a) / 2 := by ring

_ = (a - a) / 2 := by rw [h1]

_ = 0 := by ring

calc

x = a ^ 2 := by rw [ha1]

_ = 0 ^ 2 := by rw [h2]

_ = 0 := by ring

4.3.4. Example

The following is an important theorem about the integers, which we will prove later in the book, in the exercises to Section 6.6.

Theorem (the Division Algorithm)

Let \(a\) and \(b\) be integers, with \(b\) positive. Then there exists a unique integer \(r\) between 0 (inclusive) and \(b\) (exclusive), such that \(a\equiv r\mod b\).

This lemma is what allows us to do case divisions according to congruence class modulo \(b\)

(the Lean tactic mod_cases). But it’s actually a bit more powerful, since the “uniqueness” part

of the statement provides extra information.

In the Lean library it is available in the following form:

lemma Int.existsUnique_modEq_lt (a b : ℤ) (h : 0 < b) :

∃! r : ℤ, 0 ≤ r ∧ r < b ∧ a ≡ r [ZMOD b] :=

To understand this theorem better, let’s prove just one of the infinitely many cases of this theorem.

Problem

Show that there exists a unique integer \(r\), such that \(0\le r < 5\) and \(14\equiv r\mod 5\).

Solution

We will show that the unique integer with this property is 4.

First, we show that 4 has this property. It is true that \(0\le 4 < 5\), and since \(14 - 4 = 5 \cdot 2\) it is true that \(14\equiv r\mod 5\).

Now, let \(r\) be an integer for which \(0\le r < 5\) and \(14\equiv r\mod 5\). Then there exists an integer \(q\) such that \(14-r=5q\).

We have,

so since \(5\) is positive, \(1<q\). Similarly, we have

and so since \(5\) is positive, \(q<3\).

Therefore \(q\) must be 2, the only integer strictly between 1 and 3. So \(r=14-5\cdot 2=4\).

example : ∃! r : ℤ, 0 ≤ r ∧ r < 5 ∧ 14 ≡ r [ZMOD 5] := by

use 4

dsimp

constructor

· constructor

· numbers

constructor

· numbers

use 2

numbers

intro r hr

obtain ⟨hr1, hr2, q, hr3⟩ := hr

have :=

calc

5 * 1 < 14 - r := by addarith [hr2]

_ = 5 * q := by rw [hr3]

cancel 5 at this

have :=

calc

5 * q = 14 - r := by rw [hr3]

_ < 5 * 3 := by addarith [hr1]

cancel 5 at this

interval_cases q

addarith [hr3]

4.3.5. Exercises

Show that there exists a unique rational number \(x\), such that \(4x-3=9\).

example : ∃! x : ℚ, 4 * x - 3 = 9 := by sorry

Show that there exists a unique natural number \(n\), such that for all natural numbers \(a\), we have \(n\le a\).

example : ∃! n : ℕ, ∀ a, n ≤ a := by sorry

Show that there exists a unique integer \(r\), such that \(0\le r < 3\) and \(11\equiv r\mod 3\).

example : ∃! r : ℤ, 0 ≤ r ∧ r < 3 ∧ 11 ≡ r [ZMOD 3] := by sorry

4.4. Contradictory hypotheses

4.4.1. Example

Sometimes, we encounter a situation with two contradictory hypotheses. At this point, there is no need to prove anything more. Two contradictory hypotheses mean that the situation we had hypothesized can’t actually happen.

It is quite common to encounter this when giving a proof by cases. You might reduce the problem to some list of cases, prove your goal in some of those cases, and prove that the other cases are impossible.

Here is an example of this kind of reasoning. I have written the solution very pedantically, to make the point clearer.

Lemma

Let \(x\) and \(y\) be real numbers, and suppose that \(0<xy\) and \(0 \le x\). Show that \(0<y\).

We have used this fact many times before – it is one of the facts which underlie the cancel

tactic.

Proof

We consider two cases, depending on whether or not \(y\) is positive.

Case 1 (\(y \le 0\)): Since \(0 \le x\), we have that

and so it is false that \(0<xy\). This contradicts the hypothesis that \(0< xy\), so this case can’t happen.

Case 2 (\(0 < y\)): This is what we needed to prove, so we are done.

In Lean, the tactic contradiction concludes a (part of a) proof by pointing out two

contradictory hypotheses. In the Lean translation of this example, notice that right before it’s

used, the goal state is

y x : ℝ

h : 0 < x * y

hx : 0 ≤ x

hneg : y ≤ 0

this : ¬0 < x * y

⊢ 0 < y

which contains the contradictory hypotheses h : 0 < x * y and this : ¬0 < x * y. (Remember

that ¬ is the logical symbol for “not”. If you don’t name a hypothesis, Lean labels it

this.)

example {y : ℝ} (x : ℝ) (h : 0 < x * y) (hx : 0 ≤ x) : 0 < y := by

obtain hneg | hpos : y ≤ 0 ∨ 0 < y := le_or_lt y 0

· -- the case `y ≤ 0`

have : ¬0 < x * y

· apply not_lt_of_ge

calc

0 = x * 0 := by ring

_ ≥ x * y := by rel [hneg]

contradiction

· -- the case `0 < y`

apply hpos

4.4.2. Example

One very common way to get a contradiction is by proving that the hypotheses imply some “obviously

false” numeric fact, whose falseness can be checked with numbers.

Problem

Let \(t\) be an integer which is less than 3, and suppose that \(t - 1 = 6\). Show that \(t=13\).

Solution

We have,

But clearly it’s false that \(7 <3\), contradiction. So any conclusion (including \(t=13\)) is true.

You can write this proof up in Lean directly using the contradiction tactic, as in the previous

examples:

example {t : ℤ} (h2 : t < 3) (h : t - 1 = 6) : t = 13 := by

have H :=

calc

7 = t := by addarith [h]

_ < 3 := h2

have : ¬(7 : ℤ) < 3 := by numbers

contradiction

But the pattern is also sufficiently common that there is a shorthand in Lean. If H is a

hypothesis whose negation can be proved by numbers, then writing numbers at H will

close the goal.

example {t : ℤ} (h2 : t < 3) (h : t - 1 = 6) : t = 13 := by

have H :=

calc

7 = t := by addarith [h]

_ < 3 := h2

numbers at H -- this is a contradiction!

4.4.3. Example

Problem

Show that if \(n^2+n+1\equiv 1\mod 3\) then \(n\equiv 0\mod 3\) or \(n\equiv 2\mod 3\).

Solution

We consider cases according to the residue of \(n\) modulo 3. If \(n\equiv 0\mod 3\) or \(n\equiv 2\mod 3\), then we are done. Otherwise, \(n\equiv 1\mod 3\), so

contradiction.

Notice that in the above proof we did some extra work to get \(0\equiv 1\mod 3\) for the contradiction, rather than \(3\equiv 1\mod 3\), which could have been obtained more easily:

For the purposes of this book, we will treat as “obviously true/false” only congruences \(i\equiv j\mod n\) for which \(0 \le i<n\) and \(0 \le j<n\). We will ask that congruences involving larger numbers be explicitly reduced modulo \(n\), as we did here in reducing \(3=1 ^ 2 + 1 + 1\) to \(0 + 3 \cdot 1\) modulo 3 and thus to \(0\).

The mathematical justification for this is the uniqueness lemma Int.existsUnique_modEq_lt,

discussed in Example 4.3.4.

example (n : ℤ) (hn : n ^ 2 + n + 1 ≡ 1 [ZMOD 3]) :

n ≡ 0 [ZMOD 3] ∨ n ≡ 2 [ZMOD 3] := by

mod_cases h : n % 3

· -- case 1: `n ≡ 0 [ZMOD 3]`

left

apply h

· -- case 2: `n ≡ 1 [ZMOD 3]`

have H :=

calc 0 ≡ 0 + 3 * 1 [ZMOD 3] := by extra

_ = 1 ^ 2 + 1 + 1 := by numbers

_ ≡ n ^ 2 + n + 1 [ZMOD 3] := by rel [h]

_ ≡ 1 [ZMOD 3] := hn

numbers at H -- contradiction!

· -- case 3: `n ≡ 2 [ZMOD 3]`

right

apply h

4.4.4. Example

We defined prime numbers in Example 4.1.8, and proved that 2 was prime. Let’s now prove a slight reformulation of the definition, which will be convenient in showing that other numbers are prime.

Lemma

Let \(p\) be a natural number greater than or equal to 2. Suppose that for all natural numbers \(m\) for which \(1<m<p\), it is not true that \(m\) is a factor of \(p\). Show that \(p\) is prime.

Proof

Since we are given that \(2 \le p\), what’s left is to prove the second part of the definition “prime”: let \(m\) be a factor of \(p\) (\(\star\)); we must show that \(m=1\) or \(m=p\).

Since \(m\) is a factor of \(p\), we have that \(1 \le m\). So either \(m=1\) or \(1<m\); we consider cases accordingly.

Case 1 (\(m=1\)): This immediately gives our goal that \(m=1\) or \(m=p\).

Case 2 (\(1<m\)): Since \(m\) is a factor of \(p\), we have that \(m \le p\). So either \(m=p\) or \(m<p\); we consider cases accordingly.

Case 2(i) (\(m=p\)): This immediately gives our goal that \(m=1\) or \(m=p\).

Case 2(ii) (\(m<p\)): We have now established that \(1<m<p\), and by one of the facts given in the problem statement, this means that \(m\) is not a factor of \(p\). This contradicts the earlier statement (\(\star\)).

I’ve filled in about half of this proof in Lean; fill in the rest, including the final contradiction. If you need to look up the Lean names for the size bounds on factors, they were proved in Example 3.2.7 and Example 3.2.8.

example {p : ℕ} (hp : 2 ≤ p) (H : ∀ m : ℕ, 1 < m → m < p → ¬m ∣ p) : Prime p := by

constructor

· apply hp -- show that `2 ≤ p`

intro m hmp

have hp' : 0 < p := by extra

have h1m : 1 ≤ m := Nat.pos_of_dvd_of_pos hmp hp'

obtain hm | hm_left : 1 = m ∨ 1 < m := eq_or_lt_of_le h1m

· -- the case `m = 1`

left

addarith [hm]

-- the case `1 < m`

sorry

We record this for future use under the Lean name prime_test.

Here’s an example of how this prime-testing lemma is used.

Problem

Show that 5 is prime.

Solution

Clearly \(2 ≤ 5\). Let \(m\) be a natural number with \(1<m<5\). We must show that 5 is not a multiple of \(m\). There are three cases to check:

Case 1 (\(m=2\)): Since 5 lies between the consecutive multiples \(2\cdot 2\) and \(2 \cdot 3\) of 2, it is not a multiple of 2.

Case 2 (\(m=3\)): Since 5 lies between the consecutive multiples \(3\cdot 1\) and \(3 \cdot 2\) of 3, it is not a multiple of 3.

Case 3 (\(m=4\)): Since 5 lies between the consecutive multiples \(4\cdot 1\) and \(4 \cdot 2\) of 4, it is not a multiple of 4.

example : Prime 5 := by

apply prime_test

· numbers

intro m hm_left hm_right

apply Nat.not_dvd_of_exists_lt_and_lt

interval_cases m

· use 2

constructor <;> numbers

· use 1

constructor <;> numbers

· use 1

constructor <;> numbers

Here constructor <;> numbers is a shorthand for

constructor

· numbers

· numbers

More generally, <;> connects two tactics, performing the second one on every goal created by the

first one.

4.4.5. Example

Here’s a harder example, with many cases.

Problem

Let \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\) be positive natural numbers satisfying \(a^2+b^2=c^2\). Show that \(3 \le a\).

Three numbers satisfying this equation are called a Pythagorean triple, since by Pythagoras’ theorem this means that they form the three sides of a right-angled triangle. The natural numbers 3, 4, 5 satisfy this equation: \(3^2+4^2=5^2\). There are other solutions, like 5, 12, 13, but we are showing in this problem that 3, 4, 5 is the smallest solution.

Solution

Either \(a \le 2\) or \(3 \le a\). If \(3 \le a\) then we are done. We will derive a contradiction if \(a \le 2\).

Either \(b \le 1\) or \(2 \le b\). We will consider these two cases separately.

Case 1 (\(b \le 1\)):

We have that

This implies that \(c<3\). We now have upper bounds \(a \le 2\), \(b \le 1\), \(c < 3\), so \(a\) is 1 or 2, \(b\) is 1, and \(c\) is 1 or 2. We can analyze all these cases and check they don’t work:

Case 2 (\(2 \le b\)):

We have that

so \(b<c\), so \(b+1\le c\). But also

so \(c<b+1\), so it is false that \(b+1\le c\). These two facts contradict each other.

Write this proof up in Lean. It will be long; my version is 27 lines.

example {a b c : ℕ} (ha : 0 < a) (hb : 0 < b) (hc : 0 < c)

(h_pyth : a ^ 2 + b ^ 2 = c ^ 2) : 3 ≤ a := by

sorry

4.4.6. Exercises

Let \(x\) and \(y\) be real numbers, with \(x\) nonnegative, and let \(n\) be a positive natural number. Prove that if \(y^n \le x^n\) then \(y\le x\).

We have used this fact before; it’s another of the lemmas which underlie the

canceltactic.example {x y : ℝ} (n : ℕ) (hx : 0 ≤ x) (hn : 0 < n) (h : y ^ n ≤ x ^ n) : y ≤ x := by sorry

Show that if \(n^2\equiv 4\mod 5\) then \(n\equiv 2\mod 5\) or \(n\equiv 3\mod 5\).

example (n : ℤ) (hn : n ^ 2 ≡ 4 [ZMOD 5]) : n ≡ 2 [ZMOD 5] ∨ n ≡ 3 [ZMOD 5] := by sorry

Show that 7 is prime.

example : Prime 7 := by sorry

Give a different proof of a problem from the exercises to Section 2.1: Let \(x\) be a rational number whose square is 4, and which is greater than 1. Show that \(x=2\).

Instead of using the

canceltactic, give a direct proof using the ideas of this section: break into two cases, and then rule out one of them. (You may find it convenient to deduce a numeric contradiction.)example {x : ℚ} (h1 : x ^ 2 = 4) (h2 : 1 < x) : x = 2 := by have h3 := calc (x + 2) * (x - 2) = x ^ 2 + 2 * x - 2 * x - 4 := by ring _ = 0 := by addarith [h1] rw [mul_eq_zero] at h3 sorry

Show that a prime number is either 2 or odd.

example (p : ℕ) (h : Prime p) : p = 2 ∨ Odd p := by sorry

4.5. Proof by contradiction

4.5.1. Example

Problem

Show that it is not true that for all real numbers \(x\), we have \(x^2\geq x\).

Solution

Suppose that for all real numbers \(x\), we have \(x^2\geq x\). Then in particular \(0.5^2\geq 0.5\), but this is false, contradiction.

example : ¬ (∀ x : ℝ, x ^ 2 ≥ x) := by

intro h

have : 0.5 ^ 2 ≥ 0.5 := h 0.5

numbers at this

4.5.2. Example

Problem

Show that 13 is not a multiple of 3.

In the past we have established non-divisibility facts using the theorem

Nat.not_dvd_of_exists_lt_and_lt. But now we finally have the tools to do this from first

principles.

Solution

Suppose that 13 were a multiple of 3. Then there would exist a natural number \(k\) such that \(13=3k\).

Case 1, \(k \le 4\): Then

contradiction.

Case 2, \(k \ge 5\): Then

contradiction.

example : ¬ 3 ∣ 13 := by

intro H

obtain ⟨k, hk⟩ := H

obtain h4 | h5 := le_or_succ_le k 4

· have h :=

calc 13 = 3 * k := hk

_ ≤ 3 * 4 := by rel [h4]

numbers at h

· sorry

4.5.3. Example

Problem

Let \(x\) and \(y\) be real numbers and suppose that \(x+y=0\). Show that it is not possible for both \(x\) and \(y\) to be positive.

Solution

Suppose that \(x\) and \(y\) were both positive. Then

contradiction.

example {x y : ℝ} (h : x + y = 0) : ¬(x > 0 ∧ y > 0) := by

intro h

obtain ⟨hx, hy⟩ := h

have H :=

calc 0 = x + y := by rw [h]

_ > 0 := by extra

numbers at H

4.5.4. Example

Problem

Show that there does not exist a natural number \(n\), such that \(n^2=2\).

(Compare this with Example 2.3.2.)

Solution

Suppose that some integer \(n\) satisfied \(n^2=2\).

Case 1, \(n \le 1\): Then

contradiction.

Case 2, \(n \ge 2\): Then

contradiction.

example : ¬ (∃ n : ℕ, n ^ 2 = 2) := by

sorry

4.5.5. Example

Lemma

Show that an integer \(n\) is even if and only if it is not odd.

Proof

First, let \(n\) be even, and suppose that it were also odd. Then \(n\equiv 0\mod 2\) but also \(n\equiv 1\mod 2\). So

contradiction.

Now, suppose that \(n\) is not odd. Since \(n\) has to be either even or odd, it is even.

We record this for future use in Lean problems under the name Int.even_iff_not_odd.

example (n : ℤ) : Int.Even n ↔ ¬ Int.Odd n := by

constructor

· intro h1 h2

rw [Int.even_iff_modEq] at h1

rw [Int.odd_iff_modEq] at h2

have h :=

calc 0 ≡ n [ZMOD 2] := by rel [h1]

_ ≡ 1 [ZMOD 2] := by rel [h2]

numbers at h -- contradiction!

· intro h

obtain h1 | h2 := Int.even_or_odd n

· apply h1

· contradiction

Now repeat the process to characterise “not-even.”

Lemma

Show that an integer \(n\) is odd if and only if it is not even.

example (n : ℤ) : Int.Odd n ↔ ¬ Int.Even n := by

sorry

4.5.6. Example

Problem

Let \(n\) be an integer. Show that \(n^2\not\equiv 2 \mod 3\).

Solution

Suppose that \(n^2\equiv 2 \mod 3\). We consider cases according to the residue of \(n\) modulo 3.

If \(n\equiv 0 \mod 3\), then

contradiction.

If \(n\equiv 1 \mod 3\), then

contradiction.

Finally, if \(n\equiv 2 \mod 3\), then

contradiction.

example (n : ℤ) : ¬(n ^ 2 ≡ 2 [ZMOD 3]) := by

intro h

mod_cases hn : n % 3

· have h :=

calc (0:ℤ) = 0 ^ 2 := by numbers

_ ≡ n ^ 2 [ZMOD 3] := by rel [hn]

_ ≡ 2 [ZMOD 3] := by rel [h]

numbers at h -- contradiction!

· sorry

· sorry

4.5.7. Example

We can now pay a couple of debts. First, there is this theorem, first mentioned in Example 4.1.9:

Theorem

Let \(p\), \(k\) and \(l\) be natural numbers, with \(k\ne 1\), \(k\ne p\), and \(p=kl\). Then \(p\) is not prime.

Proof

\(k\) is a factor of \(p\). If \(p\) were prime, then by definition for any factor \(x\) of \(p\) either \(x=1\) or \(x=p\), so in particular \(k=1\) or \(k=p\). But either of these contradicts a hypothesis.

example {p : ℕ} (k l : ℕ) (hk1 : k ≠ 1) (hkp : k ≠ p) (hkl : p = k * l) :

¬(Prime p) := by

have hk : k ∣ p

· use l

apply hkl

intro h

obtain ⟨h2, hfact⟩ := h

have : k = 1 ∨ k = p := hfact k hk

obtain hk1' | hkp' := this

· contradiction

· contradiction

4.5.8. Example

Secondly, there is this theorem, first mentioned in Example 3.2.6:

Theorem

Let \(a\) and \(b\) be integers. If there exists an integer \(q\) such that \(bq<a<b(q + 1)\), then \(a\) is not a multiple of \(b\).

This is the lemma we have invoked in Lean as Int.not_dvd_of_exists_lt_and_lt.

Proof

Suppose for the sake of contradiction that \(a\) is a multiple of \(b\). Then there exists an integer \(k\) such that \(a=bk\). Also, let \(q\) be an integer such that \(b q<a<b(q + 1)\).

We first note that

Now let us reason from the two known inequalities separately. We first observe that

and so (since \(b>0\)) we have \(k < q+1\).

We next observe that

and so (since \(b>0\)) we have \(q < k\), thus \(q+1 \le k\).

These two facts contradict each other, so \(a\) must not be a multiple of \(b\) after all.

example (a b : ℤ) (h : ∃ q, b * q < a ∧ a < b * (q + 1)) : ¬b ∣ a := by

intro H

obtain ⟨k, hk⟩ := H

obtain ⟨q, hq₁, hq₂⟩ := h

have hb :=

calc 0 = a - a := by ring

_ < b * (q + 1) - b * q := by rel [hq₁, hq₂]

_ = b := by ring

have h1 :=

calc b * k = a := by rw [hk]

_ < b * (q + 1) := hq₂

cancel b at h1

sorry

4.5.9. Example

We also establish a test for primality which will be more efficient than the test from Example 4.4.4.

Theorem

Let \(p\) be a natural number which is at least 2. Let \(T\) be another natural number, whose square is greater than \(p\), and suppose that every natural number \(m\) for which \(1<m<T\) is not a factor of \(p\). Then \(p\) is prime.

(Notice that in the Example 4.4.4 test we had to check that every number up to \(p\) was not a factor of \(p\); with this test we only need to check the numbers up to approximately the square root of \(p\).)

Proof

By the prime test from Example 4.4.4, it suffices to show that every natural number \(m\) with \(1<m<p\) is not a factor of \(p\). Let \(m\) be such a natural number. If \(m < T\) then by hypothesis \(m\) is not a factor of \(p\).

So suppose that \(T \le m\), and that \(m\) is a factor of \(p\). Then there exists a natural number \(l\) such that \(p= ml\). The natural number \(l\) is a factor of \(p\), too.

We claim that \(1<l\). It will suffice to show that \(m \cdot 1 < ml\), and indeed,

We also claim that \(l<T\). It will suffice to show that \(Tl < T \cdot T\), and indeed,

Since we have established that \(1<l<T\), by hypothesis \(l\) is not a factor of \(p\), contradiction. So \(m\) must not be a factor of \(p\) after all.

example {p : ℕ} (hp : 2 ≤ p) (T : ℕ) (hTp : p < T ^ 2)

(H : ∀ (m : ℕ), 1 < m → m < T → ¬ (m ∣ p)) :

Prime p := by

apply prime_test hp

intro m hm1 hmp

obtain hmT | hmT := lt_or_le m T

· apply H m hm1 hmT

intro h_div

obtain ⟨l, hl⟩ := h_div

have : l ∣ p

· sorry

have hl1 :=

calc m * 1 = m := by ring

_ < p := hmp

_ = m * l := hl

cancel m at hl1

have hl2 : l < T

· sorry

have : ¬ l ∣ p := H l hl1 hl2

contradiction

We record this for future use under the Lean name better_prime_test.

Here’s an example of how this prime-testing lemma is used. I have left some of the later cases for you to check.

Problem

Show that 79 is prime.

Solution

Clearly \(2 ≤ 79\). Also notice that \(79<9^2\). Let \(m\) be a natural number with \(1<m<9\). We will show that 79 is not a multiple of \(m\). There are seven cases to check:

Case 1 (\(m=2\)): Since 79 lies between the consecutive multiples \(2\cdot 39\) and \(2 \cdot 40\) of 2, it is not a multiple of 2.

Case 2 (\(m=3\)): Since 79 lies between the consecutive multiples \(3\cdot 26\) and \(3 \cdot 27\) of 3, it is not a multiple of 3.

Case 3 (\(m=4\)): Since 79 lies between the consecutive multiples \(4\cdot 19\) and \(4 \cdot 20\) of 4, it is not a multiple of 4.

(etc. for 5, 6, 7 and 8)

example : Prime 79 := by

apply better_prime_test (T := 9)

· numbers

· numbers

intro m hm1 hm2

apply Nat.not_dvd_of_exists_lt_and_lt

interval_cases m

· use 39

constructor <;> numbers

· use 26

constructor <;> numbers

· use 19

constructor <;> numbers

· sorry

· sorry

· sorry

· sorry

4.5.10. Exercises

Show that there does not exist a real number \(t\), such that \(t \le 4\) and \(t\geq 5\).

example : ¬ (∃ t : ℝ, t ≤ 4 ∧ t ≥ 5) := by sorry

Show that there does not exist a real number \(a\), such that \(a^2 \le 8\) and \(a^3\geq 30\).

example : ¬ (∃ a : ℝ, a ^ 2 ≤ 8 ∧ a ^ 3 ≥ 30) := by sorry

Show that 7 is not even.

example : ¬ Int.Even 7 := by sorry

Let \(n\) be an integer satisfying \(n+3=7\). Show that \(n\) cannot be both even and a solution to \(n^2=10\).

example {n : ℤ} (hn : n + 3 = 7) : ¬ (Int.Even n ∧ n ^ 2 = 10) := by sorry

Let \(x\) be a real number satisfying \(x^2<9\). Show that \(x\) cannot be either less than or equal to -3, or greater than or equal to 3.

example {x : ℝ} (hx : x ^ 2 < 9) : ¬ (x ≤ -3 ∨ x ≥ 3) := by sorry

Show that there does not exist a natural number \(N\), such that every natural number greater than \(N\) is even.

example : ¬ (∃ N : ℕ, ∀ k > N, Nat.Even k) := by sorry

Let \(n\) be an integer. Show that \(n^2\not\equiv 2 \mod 4\).

example (n : ℤ) : ¬(n ^ 2 ≡ 2 [ZMOD 4]) := by sorry

Show that 1 is not prime.

We record this lemma for future use under the name

not_prime_one.example : ¬ Prime 1 := by sorry

Show that 97 is prime.

example : Prime 97 := by sorry